It began in Australia in 2020. We were in Victoria, and air B n B on the plains. We had travelled from NSW, where the bushfires were raging. Down in Sydney, you could barely see the Harbour Bridge for the smoke; you could hardly breathe. The Sydney Morning Herald was using the phrase “mega blaze” The Blue Mountains had become ash; at least 35 people were killed, including 12 firefighters. Hundreds more would die later from smoke-related conditions. Grass fires on the plains of Victoria were moving at 30 miles an hour. Heatwave, drought and winds. The Book of Revelations wasn’t even close. Our little B n B was remote, outside hundreds of miles of haze. I was invited to a pool party at the in-laws, with shade, cool water, and children’s laughter, but bowed out. Then, I regretted it. Then, an hour later, I wrote one word in my notebook. ‘Nathaniel.’

Nathaniel was a chartist in England, the West Riding of Yorkshire. It’s August 1842—the movement’s high point. More than 3 million working people have signed a petition demanding the vote. Parliament has dismissed it, and he and thousands of other mill workers are part of a general strike sweeping the north. This much I knew, but Nathaniel refused to say a word to me for at least a week or more. I made his life harder for him. A son who had died of typhus, a wife who blamed him, an employer who cuts his wages, sacks him, and a magistrate who imprisons him—still not a peep. At least I knew he was stubborn.

We flew back to Sydney. It smelt as if the entire population was having a barbecue. Shops in the mall were asking for donations for firefighters. We got a train up to the Blue Mountains to see our friends Russ and Cathy, their house on the margins of the fires. They have been volunteer firefighters for a number of years. A surprising number of firefighters are residents in danger zones. Russ took us out for a walk along a road built by convict labour in the 19th century. He had been campaigning to have it protected and its heritage marked. He is descended from a machine breaker, a Berkshire Luddite transported in the 1830s. Aussie royalty. It was it turns out the Luddites inspired Nathaniel.

We took a drive through the mountains. There is a particular kind of ash. Every tree was black but many still had leaves. The fire starts inside the tree. They were still rooted to the ground, as if they didn’t know they’d been burned. The red earth gone grey. The landscape stripped of its pastel shades. Eucalyptus trees are immediately all the same and all unique but the light can’t help the charred hills. It’s death. A swamp of ash.

The King James Bible has always been with me. Teachers planted it there. The Boys Brigade, my mother, too, was a Northern Irish protestant. It’s poetry, history and non-history, prophecies and lessons. As such, all catastrophes are about some event in the Old Testament, but nothing comparable came to mind.

In the mid-nineteenth century, religion and politics were inseparable. Nathaniel, I knew, was no Anglican and had, in all probability, estranged himself from the nearest non-conformist chapel but not the Bible. And then suddenly, there was Sarah, his wife, wooed by a Methodist preacher and invited to teach at a Wesleyan school. She chose Noah.

“And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth. Destroy both man and beast and the creeping thing and the fowls of the air, for it repenteth me that I have made them. But Noah, found grace in the eyes of the Lord. Noah was just a man and perfect in his generations and Noah walked with God. The earth was corrupt before God. The earth was filled with violence. And God said to Noah, The end of all flesh has come before me. And behold I do bring a flood of waters upon the earth to destroy all flesh, wherein is the breath of life from under heaven, and everything that is in the earth shall die.”

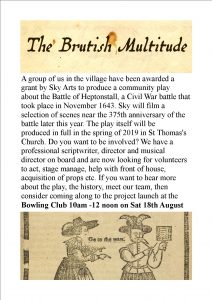

As soon as Nathaniel heard this, I couldn’t shut him up. A first draft was done before we were on the plane home. Four years later, last night was the opening night of a four-show run at Halifax Playhouse. It went well, the cast is terrific, the audience was substantial enough, and there’ll be a hundred or so in tonight. Britain’s chartists were far-sighted and prophetic; it was our civil rights movement, a century ahead of elsewhere, just like our revolution of the 1640s. They are the cornerstone of my patriotism, which has nothing to do with the Union Jack, the Proms or Nigel Farage and everything to do with Blake, Orwell, Ben Ruhston and Mary Woolstencroft. I spoke to many of the audience yesterday evening; they had plenty to say, the common thread being, ‘Why isn’t there more working-class history at the theatre?’